Unwilling or Unable? Measuring Anti-Asian Implicit Biases of Pre-Service Teachers in Order to Impact Teacher Effectiveness

Nicholas D. Hartlep

Educational Administration and Foundations • Illinois State University

Educational Administration and Foundations • Illinois State University

Nicholas D. Hartlep is an Assistant Professor of Educational Foundations at Illinois State University. He is Series Editor of the “Urban Education Studies” book series with Information Age Publishing. In 2015 he was awarded the University Research Initiative (URI) Award from Illinois State University for his research productivity and contribution. He is author of The Model Minority Stereotype: Demystifying Asian American Success (2013), editor of Modern Societal Impacts of the Model Minority Stereotype (2015) and The Model Stereotype Reader: Critical and Challenging Readings for the 21st Century (2014), and co-editor of The Assault on Communities of Color: Exploring the Realities of Race-Based Violence (2015) and Unhooking from Whiteness: The Key to Dismantling Racism in the United States (2013).

Keywords: Implicit association tests, Asian stereotypes, pre-service teacher education

This exploratory scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) study analyzes undergraduate students’ performances on an Implicit Association Test (IAT). The purpose of this exploratory SoTL study was to measure the levels of implicit bias that two groups of pre-service teachers held toward Asian Americans. Two sections of students in a Social Foundations of Education course took an Asian IAT at the beginning and ending of a 6-week summer session. This research examined what students attributed their IAT results to. Family, friends, and upbringing (environmental and external) were salient attributions across both sections of the Social Foundations of Education course as determined by pre- and post-IAT writing assignments. Students’ justifications did not change during the 6-week course, which may show that students believe their biases are what they are, suggesting they don’t feel bad that they may harbor anti-Asian biases.

The Need for Culturally Relevant Teachers

K–12 classrooms in the United States are transforming, quickly becoming more multicultural and multilingual, largely the result of immigration and glocal[1] sociopolitical factors (Barbour & Barbour, 1997). However, despite classrooms becoming more heterogeneous and diverse, our K–12 teaching force remains largely homogeneous in composition. Recent statistics document that 81.9% of our nation’s K–12 teachers are non-Hispanic White, while 76.3% are female (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2012a, 2012b). The result of these racial, cultural, gender, and language imbalances is that mismatches between students and their teachers are inevitable, becoming more and more frequent, and requiring more culturally relevant practitioners who can teach under such conditions (Sleeter, Neal, & Kumashiro, 2015). Moreover, the need to prepare culturally relevant teachers has quickly become grist for the mill for teacher educators. Teacher education scholars and policymakers refer to these teacher-student mismatches in more holistic terms, embodying what they call a “demographic imperative” for United States education. Below I discuss the demographic imperative and its relationship to the present research.

The Demographic Imperative

The demographic imperative is one of many reasons that there is an urgent need for culturally relevant K–12 teachers in the United States (Haberman & Post, 1998; Hartlep & Joseph, 2014). Under the present circumstances of the demographic imperative, research has documented that culturally relevant K–12 teachers are capable of drawing on student diversity, in all its forms, in the classroom, treating it as an asset, in order to teach using pedagogies that are equitable, anti-biased, and anti-racist. For instance, Haberman (1991, 2004, 2012) documents that effective teachers are those individuals who understand that there are immediate and long-term consequences to teaching and learning, especially when it comes to what teachers say and believe about their students. Specifically, Haberman (1991) states that effective teachers are not moral judges but understand that students become “at-risk” not because of poverty or pathology but because of ineffective teachers. As a result, according to Haberman’s research, effective teachers take ownership for their students’ learning and do not blame children’s circumstances (e.g., poverty, a culture of poverty, uneducated parents/guardians, etc.). Haberman’s research on effective K–12 teachers’ dispositions is important to consider for pre-service teacher education, and it informed the present study (e.g., see Haberman, 1991, 2004, 2012; Haberman & Post, 1998).

For instance, if K–12 teachers misjudge their students, believe in a “culture of poverty” (Gorski, 2008; Payne, 2005), utilize “deficit” lenses (Valencia, 2010), and are unaware of their own hidden “implicit biases” (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013) when teaching students, they may unwittingly adopt what Haberman (1991) identifies as the “pedagogy of poverty.” The “pedagogy of poverty” is an unintended consequence of in-service teachers holding low standards and expectations for student learning and achievement. Teachers who enact teaching/learning activities that resemble teaching in the classroom manifest the pedagogy of poverty. The unfortunate reality is that the pedagogy of poverty has little-to-no educative value for students. Teacher educators need to understand the attitudes of pre-service teachers because the odds are high that a K–12 teacher will have to teach students who are culturally, racially, and/or linguistically different than him/herself. It can be damaging to the learning of future students if pre-service teachers leave teacher education harboring implicit biases, never having had to deal with them and the “threshold concepts” (Meyer & Land, 2005) and “cognitive bottlenecks” (Gorski, Zenkov, Osei-Kofi, & Sapp, 2013) they are built upon. According to Gorski, Zenkov, Osei-Kofi, and Sapp (2013), cognitive bottlenecks are “the foundational concepts and competencies—the threshold concepts and competencies—that will bolster [pre-service teachers’] development as equity- and justice-minded educators” (p. 2, italics original). Next I share why studying pre-service teachers’ implicit bias toward Asian Americans is noteworthy given the context of the “demographic imperative.”

Pre-Service Teachers’ Implicit Bias Toward Asian American Students

The experiences of Asian American K–12 students remain overlooked, and there is a dearth of studies that have examined this population’s schooling experience (cf. Ooka Pang & Cheng, 1998). One possible explanation for the shortage of research conducted on the Asian American population, when compared to other student populations, such as African American and Hispanic/Latino populations, is that the Asian American K–12 student population, albeit growing, represents a small fraction of the overall K–12 student population. For instance, after analyzing 2010 U.S. Census Data, Toldson (2011) reports that Asian American male and female students represent a small percentage of the overall PK–12 student population: 2.17% and 2.09%, respectively. Notwithstanding, the Asian American student population is currently the fastest growing, which would indicate that this oversight is problematic.

Needed Research

Educating pre-service teachers about implicit bias is important and needed in teacher education. Because K–12 teachers are responsible for making decisions on a consistent and regular basis in the classroom, they should examine their implicit biases. Whether it is regarding classroom management or deciding the grades of students, K–12 teachers hold much influence and power in the educational/schooling process. According to Lieber (2009), “Implicit biases are hidden preferences—so hidden that we are unaware we even have them” (p. 93). Since K–12 teachers may make decisions and act in the classroom in ways that are consistent with their implicit bias, it is important that they take Implicit Association Tests (IAT) and reflect on their results during their teacher education. For example, if a teacher believes that their Asian American students are all “model minorities” who do well in school, they may overlook those students who may benefit from special education. The model minority stereotype of Asian Americans is a halo that assumes they are high achieving in school (Hartlep, 2014b).

Although teachers may “explicitly endorse egalitarian beliefs, they may be unaware that they harbor unconscious implicit biases” (Casad, Flores, & Didway, 2013, p. 118). As was already indicated in the beginning of this article, K–12 schools are becoming multicultural and more diverse every day, while the teaching force remains highly feminized and white (also arguably mono-cultural). There is no way around it: white teachers will come into contact with students who are different than themselves, and they need to be aware of the implicit biases they hold (Howard, 1999).

Purpose of This Study

The purpose of this exploratory scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) study was to measure the levels of implicit bias that two groups of pre-service teachers held toward Asian Americans. The study was exploratory in nature due to there being little or no prior research conducted on pre-service teachers’ implicit bias toward Asian Americans. As a result, this study neither made specific hypotheses to test nor made predictions to be confirmed (Stebbins, 2001). Rather, the research was carried out and intended to provide a foundation for future hypothesis generation, especially in terms of factors that may impact how to effectively teach white pre-service teachers about their own hidden biases in teacher education (Casad, Flores, & Didway, 2013). In the next section I review social scientific research that has examined stereotypes of Asians/Asian Americans.

Stereotypes of Asians/Asian Americans

Stereotypes of Asians/Asian Americans are prevalent in the United States and don’t appear to be disappearing. Hartlep (2013, 2014b, 2015) and Lee (1996) have written extensively about the “model minority” stereotype of Asians/Asian Americans in the United States, one of the more salient stereotypes of Asians within a constellation of many stereotypes. According to Hartlep (2014b), the model minority stereotype is a false generalization that Asian Americans are successful and well adjusted. Embedded within the stereotype, however, are other stereotypes of Asians that speak to issues of “social awkwardness” (Zhang, 2010), “foreignness” (Lee, Wong, & Alvarez, 2009), and cultural and sexual “objectification” (Hartlep, 2014a).

|

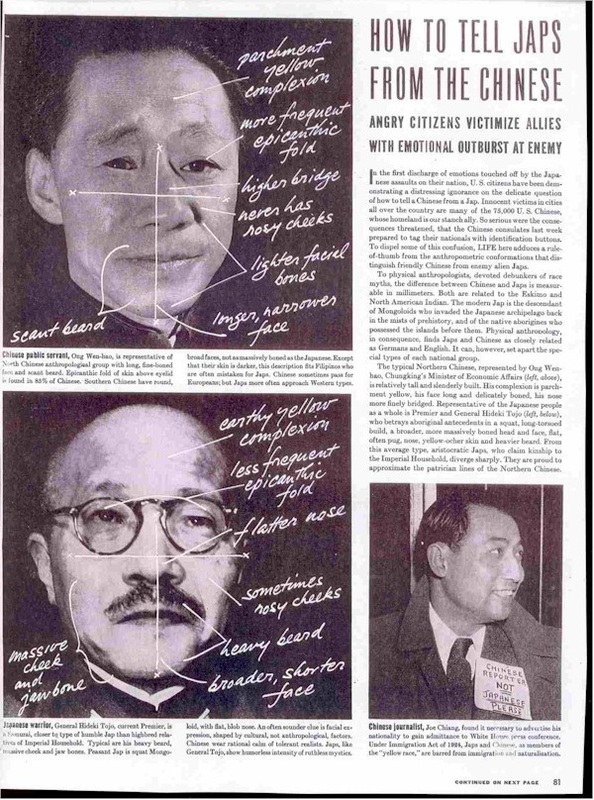

For instance, stereotypes of Asian facial features include that they have slanted eyes. Historically, Asians were stereotyped in the United States as having “buck” teeth and being a menace and disloyal to the United States, especially during the period of the World War II. The infamous case of Wen Ho Lee is an illustrative example. Dr. Lee, then a Los Alamos scientist, was falsely accused of being a spy, largely because he was Taiwanese (cf. Gotanda, 2000). Other past examples of Asian Americans being stereotyped negatively can be seen when Japanese Americans were thrown into internment camps and treated as second-class citizens, having done nothing illegal. Indeed, mainstream magazines such as Life (1941) ran stories such as “How to Tell Japs from Chinese” (see Figure 1), which illustrate the idea that in America, Asians have been seen as “foreigners.”

Stereotypes, in many ways, are mental images we have of certain people and cultures (Blair, Ma, & Lenton, 2001). It is quite possible that the stereotype of the smart Asian model minority is what first comes to mind. But, it is also quite possible that less desirable stereotypes such as a disloyal citizen or a spy might also lurk beneath supposed more “positive” stereotypes. Meanwhile, what the brain is thinking at the subconscious level is important to analyze. This is why IATs are a worthwhile as measurement tools—since individuals may not think they hold biases. In the next section I review what IATs are and why I believe they are trustworthy tools. |

Implicit Association Tests (IATs)

Although Implicit Association Tests, or IATs as they are commonly referred to for short, have been criticized that they cannot be believed (see Azar, 2008), work has established their validity and reliability (e.g., Lane, Banaji, Nosek, & Greenwald, 2007). As a result, the present research proceeded, erring on the side that the Asian IAT can be trusted and detect pre-service teachers’ implicit biases. IATs are helpful for educational researchers because they capture levels of bias that social desirability masks (e.g., usually people do not want to appear biased), as well as something that, cognitively, individuals may not be willing to disclose (e.g., people might not disclose truthfully what they feel). Hence, IATs capture an individual’s “inability” and also his/her “unwillingness” to disclose levels of bias.

The Asian stereotypes shared above surely influence an individual’s implicit bias, but by how much? Harvard University’s “Project Implicit” website has an IAT that measures individuals’ implicit bias toward Asian Americans. This website was chosen for data collection because the study was interested in measuring pre-service teachers’ level of bias toward Asians specifically. There are other IATs on the “Project Implicit” website that other researchers and future studies might consider using, such as IATs that examine: skin tone, disability, weapons, gender-science, sexuality, religion, weight, gender-career, Arab-Muslim, age, race, and Native American.

In the section that follows I share the methods that guided this exploratory study. First, I share background information on the study participants. Next, I share my analysis and findings. I conclude with a statement about study considerations and future research.

Methods

Participants

All participants (n = 44) in this study were undergraduates who were taking a 6-week summer Social Foundations of Education course. All participants were pre-service teacher education students. The course was a 200 level course, and two sections participated. IRB approval was obtained from the university prior to any research being conducted, and all participants signed informed consent forms indicating their willingness to participate. Table 1 below shares descriptive information about these two sections and the students in them.

Table 1

|

Section 1 |

Section 2 |

Male Female |

n = 9 n = 13 |

n = 3 n = 19 |

Non-Hispanic White Asian American African American |

n = 20 n = 1 n = 1 |

n = 22 n = 0 n = 0 |

| TOTAL | N = 22 | N = 22 |

Analysis

Casad, Flores, and Didway (2013) conducted a study that examined students’ criticisms of the IAT’s validity. The researchers had students complete an assignment in which students reported reasons why they believed the IAT was valid or invalid. They found that students “explained away” their IAT results in ways that were congruent with their explicit attitudes. In other words, students justified why their IAT results were what they were. Similar to Casad, Flores, and Didway, I required my students take both a pre- and a post-IAT that measured anti-Asian bias. I did so in order to determine if their justifications changed.

During the first week of the Social Foundations of Education course, students logged into the “Project Implicit” website and took the Asian IAT. A screencast was created that modeled how to access the Harvard website and explained what they should print for later use (e.g., their final IAT scores). In addition to documenting their IAT score, students were required to write a 1- to 3-page single-spaced paper explaining what their IAT result was and why they thought they received the result that they did.

During weeks two through five, students read The Model Minority Stereotype Reader: Critical and Challenging Readings for the 21st Century (Hartlep, 2014b) and answered chapter questions, posting their responses on a discussion board when complete. Students from both sections—1 and 2—posted their chapter responses. Section 1 (see Table 1 above) was required to respond to one classmate’s chapter responses, while section 2 was not required to do this; section 2 students merely needed to read, answer chapter questions, and post to the discussion board.

During the last week (the sixth) of the course, Social Foundations of Education students repeated the assignment they had done in the first week. Again, students were required to take the Asian IAT, document their score, and reflect upon their results. However, this time in their 1- to 3-page single-spaced paper they needed to address why their score changed or stayed the same. Is it possible for them to unlearn “implicit biases” just by reading The Model Minority Stereotype Reader? If their score “worsened,” that is, if their score indicated they were more biased than their pre-IAT results, they were to address what they attributed this change to. If their score improved, that is, if their post-IAT results indicated they were less biased than their pre-IAT results, they were to address what they attributed this change to.

Results

This study described an exploratory study that was designed to measure implicit bias of pre-service teachers who took a summer Social Foundations of Education course. Similar to the research of Casad, Flores, and Didway (2013), who found that “people may be unwilling to accept the IAT’s accuracy due to their disbelief that they hold prejudiced attitudes” (p. 122), I found that the majority of students—across both sections—did not acknowledge that they could be racist towards Asians/Asian Americans. This finding was consistent in the pre- and post-IAT paper assignments.

I was motivated to see if it was possible to reduce pre-service teachers’ implicit bias by reading about the Asian model minority stereotype. Below, I share quantitative findings and qualitative findings.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative analyses indicated that being required to discuss the chapter questions did not result in a reduction of anti-Asian implicit bias as measured by the IAT (pre vs. post). For example, the section that had to discuss the chapter responses had 22 students. Of those 22 students, 7 improved (had reduced anti-Asian bias according to pre-IAT vs. post-IAT). Meanwhile, the section that was not required to discuss chapter responses also had 22 students, of which 13 improved (had reduced anti-Asian bias according to pre-IAT vs. post-IAT). Despite the fact that both sections were the same course (and composed of an equal number of students), the design of the present research doesn’t permit me to ascribe causality to my findings. Although being required to discuss the chapter questions did not result in a reduction of anti-Asian implicit bias, it is possible that students’ implicit biases were reified by reading The Model Minority Stereotype Reader—a possibility that is disconcerting.[2]

Qualitative Findings

This exploratory research was also interested in determining what students attributed their IAT results to. Family, friends, and upbringing (environmental and external) were salient attributions across both sections of the Social Foundations of Education course as determined from pre- and post-IAT writing assignments. Students’ justifications did not change during the 6-week course, which is interesting, because it shows that students believe their biases are what they are, suggesting they don’t feel bad if they may harbor anti-Asian biases.

Below are some quotes taken from students’ final IAT papers.

“Overall, I believe that IAT test is a test that results from your experiences in the world, and who you are around. It does not mean that I look at Asian Americans differently or think they are below any other race. It simply means that your experiences in life really show through this test.” (White Female, Section 2)

“I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to have taken the IAT a second time because it alluded me to the difficulty society has in ignoring and overcoming the model minority stereotype and the association of Asian Americans with foreign ideals. This was conveyed in my test results despite my newfound knowledge about the harsh reality of Asian Americans. While this concept is crucial to understand generally, it is extremely beneficial for me to acknowledge as a future educator, and I will be sure to address these issues in my classroom and strive to challenge the myth of the model minority.” (White Female, Section 2)

“The first time taking the test, I thought that bias played a role in the outcome and the results. This time around, I really do not think it was the bias that was the factor.” (White Male, Section 2)

“The Project Implicit tests have shown me that no matter whom my friends are or who I date, I will never be completely unbiased about the world around me and those who pass through. This is difficult to accept when I consider myself an openhearted and personable woman. However, I have to remind myself that just because I have these biases, whether I like them or not, does not mean I act upon them.” (White Female, Section 1)

“While I think it is normal for people to identify more with their own ethnicity, as a teacher, I will be teaching multiple races, cultures, and backgrounds. I hope that by recognizing my subconscious bias towards other cultures and races I can help change not only my subconscious but also my classes. This way we can start creating a world free from stereotypes.” (White Female, Section 1)

Quotation #1 seems to indicate that being biased is something that individuals just are. Quotation #2 addresses that despite new knowledge, implicit biases are difficult to replace and/or reduce. I find Quotation #3 to be incredibly interesting. This male student went from “Strong automatic association of European American with American and Asian American with Foreign” on the first Asian IAT paper assignment to “Little to no automatic preference between ethnicity and American or Foreign” on the second Asian IAT paper assignment. The comment, “The first time taking the test, I thought that bias played a role in the outcome and the results. This time around, I really do not think it was the bias that was the factor” seems as though he wants to take credit for becoming unbiased, while initially he was apprehensive—as somehow the IAT instrument was flawed because his results indicated he was biased against Asian Americans. Quotation #4, “However, I have to remind myself that just because I have these biases, whether I like them or not, does not mean I act upon them” is counterfactual. Research documents that individuals do act on their implicit biases—something that has to be considered in cases such as the courtroom (cf. Kang et al., 2012) and, I would argue, the K–12 classroom.

Lastly, Quotation #5 speaks to the heart of this study, the demographic imperative that was introduced in the beginning of this article: “While I think it is normal for people to identify more with their own ethnicity, as a teacher, I will be teaching multiple races, cultures, and backgrounds. I hope that by recognizing my subconscious bias towards other cultures and races I can help change not only my subconscious but also my classes. This way we can start creating a world free from stereotypes.” The white female student quoted in Quotation #5 will most likely teach children of multiple races, cultures, and backgrounds, which is why understanding implicit biases is so important.

Study Considerations

Although exploratory in nature, the results of this study need to be interpreted with caution. The study’s sample (n = 44 pre-service teachers in a Social Foundations of Education course) was a limitation. For instance, the findings may not apply to Social Foundations of Education courses sampled from larger, more diverse, and heterogeneous universities or from Social Foundations of Education courses with significantly larger numbers of Asian American pre-service teachers. The present study only had one Asian American participant who was in section 1. Another limitation of the present research was that the course was only six weeks long. Because students only had four weeks between the first and the last week of the summer course, having the course last 16 weeks—which is common for Fall and Spring semesters—may have impacted the results.

Future Research

Future research may consider using “attribution theory” to test to what pre-service teachers attribute their Asian IAT scores. Although the pre-service teacher participants in this study attributed their IAT results to their family, friends, and environment, future research might seek to understand if this finding is consistent across a larger sample of students and/or within other disciplinary courses and IATs. In addition to the Asian IAT, the “Project Implicit” website has IATs that measure implicit bias about mental health, such as depression, mental illness, self-esteem, and self-harm. These sorts of non-racial IATs could easily be used by professors who teach courses in other disciplines related to K–12 teacher education, such as health, psychology, counseling, and/or special education.

References

Azar, B. (2008). IAT: Fad or fabulous? Monitor on Psychology, 39(7), 44.

Banaji, M., & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. New York: Delacorte.

Barbour, C., & Barbour, N. (1997). Families, schools, and communities: Building partnerships for educating children. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Blair, I. V., Ma, J. E., & Lenton, A. P. (2001). Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of implicit stereotypes through mental imagery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 828–841. Retrieved from http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/HomePage/Class/Psy394U/Bower/10%20Automatic%20Process/I.Blair-mod.%20stereotypes.pdf

Casad, B. J., Flores, A. J., & Didway, J. D. (2013). Using the implicit association test as an unconscious raising tool in psychology. Teaching of Psychology, 40(2), 118–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0098628312475031

Gorski, P. C. (2008). Peddling poverty for profit: Elements of oppression in Ruby Payne’s framework. Equity & Excellence in Education, 41(1), 130–148.

Gorski, P. C., Zenkov, K., Osei-Kofi, N., & Sapp, J. (Eds.). (2013). Cultivating social justice teachers: How teacher educators have helped students overcome cognitive bottlenecks and learn critical social justice. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Gotanda, N. (2000). Comparative racialization: Racial profiling and the case of Wen Ho Lee. UCLA Law Review, 47, 1689–1703.

Haberman, M. (1991). The pedagogy of poverty versus good teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 73(4), 290–94.

Haberman, M. (2004). Star teachers: The ideology and best practices of effective teachers of children and youth in poverty. Houston, TX: The Haberman Educational Foundation.

Haberman, M. (2012). Teacher talk: When teachers face themselves. Houston, TX: The Haberman Educational Foundation.

Haberman, M., & Post, L. (1998). Teachers for multicultural schools: The power of selection. Theory Into Practice, 37(2), 96–104.

Hartlep, N. D. (2013). The model minority stereotype: Demystifying Asian American success. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Hartlep, N. D. (2014a). Modern em(body)ments of the model minority in South Korea. Studies on Asia, 4(1), 108–123. Retrieved from http://studiesonasia.illinoisstate.edu/seriesIV/documents/NDHartlep_studies_march14.pdf

Hartlep, N. D. (Ed.). (2014b). The model minority stereotype reader: Critical and challenging readings for the 21st century. San Diego, CA: Cognella.

Hartlep, N. D. (Ed.). (2015). Modern societal impacts of the model minority stereotype. Hershey, PA: IGI.

Hartlep, N. D., & Joseph, T. D. (2014). Using balanced literacy for delivering culturally relevant pedagogy to prepare teachers: A 20-year perspective on Dreamkeepers. E-Journal of Balanced Literacy, 2(1), 4–9.

Howard, G. R. (1999). We can’t teach what we don't know: White teachers, multiracial schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kang, J., Bennett, M., Carbado, D., Casey, P., Dasgupta, N., Faigman, D., et al. (2012). Implicit bias in the courtroom. UCLA Law Review, 59(5), 1124–1186. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/agg/pdf/Kang&al.ImplicitBias.UCLALawRev.2012.pdf

Lane, K. A., Banaji, M. R., Nosek, B. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2007). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: IV: Procedures and validity. In B. Wittenbrink & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Implicit measures of attitudes: Procedures and controversies (pp. 59–102). New York: Guilford Press.

Lee, S. J. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lee, S. J., Wong, N. A., & Alvarez, A. N. (2009). The model minority and the perpetual foreigner: Stereotypes of Asian Americans. In N. Tewari & A. N. Alvarez (Eds.), Asian American psychology: Current perspectives (pp. 69–85). New York: Psychology Press.

Lieber, L. D. (2009). The hidden dangers of implicit bias in the workplace. Employment Relations Today, 36(2), 93–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ert.20254

How to tell Japs from Chinese. (1941, December 22). Life, 11(25), 81–82.

Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373–388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2012a). Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Table 1. Total number of public school teachers and percentage distribution of school teachers, by race/ethnicity and state: 2011–12. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/SASS/tables/sass1112_2013314_t1s_001.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2012b). Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Table 2. Average and median age of public school teachers and percentage distribution of teachers, by age category, sex, and state: 2011–12. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/SASS/tables/sass1112_2013314_t1s_002.asp

Ooka Pang, V., & Cheng, L. L. (1998). Struggling to be heard: The unmet needs of Asian Pacific American children. New York: State University of New York Press.

Payne, R. K. (2005). A framework for understanding poverty. Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Sleeter, C. E., Neal, L. I., & Kumashiro, K. K. (Eds.). (2015). Diversifying the teacher workforce: Preparing and retaining highly effective teachers. New York: Routledge.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Toldson, I. A. (2011). Editor’s comments: Diversifying the United States’ teaching force: Where are we now? Where do we need to go? How do we get there? Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 183–186.

Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. New York: Routledge.

Zhang, Q. (2010). Asian Americans beyond the model minority stereotype: The nerdy and the left out. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(1), 20–37.

Banaji, M., & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. New York: Delacorte.

Barbour, C., & Barbour, N. (1997). Families, schools, and communities: Building partnerships for educating children. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Blair, I. V., Ma, J. E., & Lenton, A. P. (2001). Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of implicit stereotypes through mental imagery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 828–841. Retrieved from http://homepage.psy.utexas.edu/HomePage/Class/Psy394U/Bower/10%20Automatic%20Process/I.Blair-mod.%20stereotypes.pdf

Casad, B. J., Flores, A. J., & Didway, J. D. (2013). Using the implicit association test as an unconscious raising tool in psychology. Teaching of Psychology, 40(2), 118–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0098628312475031

Gorski, P. C. (2008). Peddling poverty for profit: Elements of oppression in Ruby Payne’s framework. Equity & Excellence in Education, 41(1), 130–148.

Gorski, P. C., Zenkov, K., Osei-Kofi, N., & Sapp, J. (Eds.). (2013). Cultivating social justice teachers: How teacher educators have helped students overcome cognitive bottlenecks and learn critical social justice. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Gotanda, N. (2000). Comparative racialization: Racial profiling and the case of Wen Ho Lee. UCLA Law Review, 47, 1689–1703.

Haberman, M. (1991). The pedagogy of poverty versus good teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 73(4), 290–94.

Haberman, M. (2004). Star teachers: The ideology and best practices of effective teachers of children and youth in poverty. Houston, TX: The Haberman Educational Foundation.

Haberman, M. (2012). Teacher talk: When teachers face themselves. Houston, TX: The Haberman Educational Foundation.

Haberman, M., & Post, L. (1998). Teachers for multicultural schools: The power of selection. Theory Into Practice, 37(2), 96–104.

Hartlep, N. D. (2013). The model minority stereotype: Demystifying Asian American success. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Hartlep, N. D. (2014a). Modern em(body)ments of the model minority in South Korea. Studies on Asia, 4(1), 108–123. Retrieved from http://studiesonasia.illinoisstate.edu/seriesIV/documents/NDHartlep_studies_march14.pdf

Hartlep, N. D. (Ed.). (2014b). The model minority stereotype reader: Critical and challenging readings for the 21st century. San Diego, CA: Cognella.

Hartlep, N. D. (Ed.). (2015). Modern societal impacts of the model minority stereotype. Hershey, PA: IGI.

Hartlep, N. D., & Joseph, T. D. (2014). Using balanced literacy for delivering culturally relevant pedagogy to prepare teachers: A 20-year perspective on Dreamkeepers. E-Journal of Balanced Literacy, 2(1), 4–9.

Howard, G. R. (1999). We can’t teach what we don't know: White teachers, multiracial schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Kang, J., Bennett, M., Carbado, D., Casey, P., Dasgupta, N., Faigman, D., et al. (2012). Implicit bias in the courtroom. UCLA Law Review, 59(5), 1124–1186. Retrieved from http://faculty.washington.edu/agg/pdf/Kang&al.ImplicitBias.UCLALawRev.2012.pdf

Lane, K. A., Banaji, M. R., Nosek, B. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2007). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: IV: Procedures and validity. In B. Wittenbrink & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Implicit measures of attitudes: Procedures and controversies (pp. 59–102). New York: Guilford Press.

Lee, S. J. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lee, S. J., Wong, N. A., & Alvarez, A. N. (2009). The model minority and the perpetual foreigner: Stereotypes of Asian Americans. In N. Tewari & A. N. Alvarez (Eds.), Asian American psychology: Current perspectives (pp. 69–85). New York: Psychology Press.

Lieber, L. D. (2009). The hidden dangers of implicit bias in the workplace. Employment Relations Today, 36(2), 93–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ert.20254

How to tell Japs from Chinese. (1941, December 22). Life, 11(25), 81–82.

Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373–388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2012a). Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Table 1. Total number of public school teachers and percentage distribution of school teachers, by race/ethnicity and state: 2011–12. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/SASS/tables/sass1112_2013314_t1s_001.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2012b). Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS): Table 2. Average and median age of public school teachers and percentage distribution of teachers, by age category, sex, and state: 2011–12. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/SASS/tables/sass1112_2013314_t1s_002.asp

Ooka Pang, V., & Cheng, L. L. (1998). Struggling to be heard: The unmet needs of Asian Pacific American children. New York: State University of New York Press.

Payne, R. K. (2005). A framework for understanding poverty. Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Sleeter, C. E., Neal, L. I., & Kumashiro, K. K. (Eds.). (2015). Diversifying the teacher workforce: Preparing and retaining highly effective teachers. New York: Routledge.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Toldson, I. A. (2011). Editor’s comments: Diversifying the United States’ teaching force: Where are we now? Where do we need to go? How do we get there? Journal of Negro Education, 80(3), 183–186.

Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. New York: Routledge.

Zhang, Q. (2010). Asian Americans beyond the model minority stereotype: The nerdy and the left out. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 3(1), 20–37.

Footnotes

[1] In this article I use the term “glocal,” a mixture of “global” and “local,” because regional forces as well as global forces are causing changes in public schools throughout the United States.

[2] This would be disconcerting because it may mean that what I did in the 6-week course attenuated, rather than minimized, students’ anti-Asian implicit bias. It may also suggest that students’ “cognitive bottlenecks” were not overcome from reading scholarly writing about Asian stereotyping. If this is the case, Social Foundations courses may benefit from being redesigned and requiring less reading.

© 2015 Illinois State University