Transition to Standards-Based Grading: Six Steps to Implement Badging in College Courses

Mandy White

Department of Special Education • Illinois State University

Department of Special Education • Illinois State University

Tara Kaczorowski

Department of Special Education • Illinois State University

Department of Special Education • Illinois State University

Robyn Seglem

School of Teaching and Learning • Illinois State University

School of Teaching and Learning • Illinois State University

Traditional university courses assign points, which translate into letter grades, but those points earned do not always reflect the mastery of the intended learning outcomes for the course. This becomes problematic because students seem more concerned about points and grades rather than learning. We transitioned to Standards-Based Grading over several semesters and identified six steps for implementing badging in college courses: (a) familiarize and redefine course outcomes, (b) evaluate and align assignments and activities, (c) create rubrics, (d) establish a recording system for badges, (e) initiate the communication cycle, and (f) define final course grades.

Keywords: assessment, standards-based grading, badging

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mandy White, Department of Special Education, Illinois State University. Email: [email protected]

Transition to Standards-Based Grading: Six Steps to Implement Badging in College Courses

It was time to get ready for the new semester. As we looked at our current grading practices, we knew we wanted something new, different, better. We had seen several different examples of grading styles across campus. Now, we needed to think through which one made the most sense for us and our students.

Traditional university courses assign points based on the completion and/or quality of assignment submission, which then translates into letter grades by calculating a percentage of total points or a percentage based on weighted categories of points. Even with the use of rubrics, points earned do not always equate to mastery of the learning outcomes. The concept of traditional rubrics and percentages can be problematic because students seem more concerned about points rather than what they are learning. We (Mandy and Tara – first and second authors) wanted our teaching philosophy to be consistent with our grading practices, and a traditional approach did not fit. According to Marzano (2000), the American grading system is more than a century old and lacks research support. In the traditional grading system, students focus on passing courses, completion of work, and effort rather than the content and skills they gain while acquiring those grades (Adams, 2005; Tippin, Lafreniere, & Page, 2012). In a pre-course survey, we asked our students to reflect on what it means to earn an “A” in a course, and their responses echoed the findings of these researchers – students generally believed grades should be based on their effort and completion of assignments without acknowledging mastery of content.

We reflected on our own beliefs about grading and learning and analyzed different gradings systems we had experienced as students. As a doctoral student, Mandy had experienced a badging grading system while taking a course with Robyn (third author). This system aligned most to our personal teaching and assessment philosophies, so we used that system as a starting point to make the transition to a standards-based grading (SBG) system with badging. An SBG system is focused on the skills you want students to achieve within the course rather than assigning points to activities. The primary difference noted is the focus on deeper learning rather than outcome artifacts (Muñoz & Guskey, 2015). Using an SBG approach allows students to focus on what instructor feedback is communicating to them about the learning achieved in the course (Boesdorfer, Baldwin, & Lieberum, 2018). Additionally, SBG allows students to understand their strengths and areas for growth (O’Connor & Wormelli, 2011) and can help provide a coherent and uniform approach to grading (Carifio & Carey, 2009), which is useful for consistency when there are multiple sections of the same course. Our instructional context is teacher preparation, so an added benefit of aligning our grading practices with our teaching and assessment philosophies is giving teacher candidates exposure to SBG, which is becoming increasingly popular in K-12 schools (Guskey, 2001).

Our transition to SBG with badging occurred over several semesters. In early semesters of our grading evolution, we revised all rubrics to utilize standards-based language as indicator levels: Emergent, Developing, Basic, Advanced. In a traditional rubric, indicator levels are associated with numerical values (e.g., Emergent = 1; Developing = 2; Basic = 3; Advanced = 4) that are added at the end to create a total summative score on an assignment. Our initial concern with this approach was that we expect students to be at the developing or emergent levels for some skills throughout the semester, but, if developing is equal to 2 out of 4 points (i.e., 50%), then developing on a rubric item results in a failing score. We asked ourselves – at the end of the semester, if a student earned a mix of basic and developing scores on different learning outcomes, what would we expect their grade to be? Mathematically, using the scale described above, an equal split between developing and basic would result in a final grade of 62.5% – a failing grade – and this just did not sit well with us. To reconcile this, we evaluated rubrics using a conversion scale rather than by adding up points. This conversion scale (Figure 1) assigned a final grade based on how most of the rubric components were rated and served as a good first step toward SBG.

| Category | Points Earned | Description* |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced/Proficient A+ |

30 100% |

Most components fall in the Advanced/Proficient category with no scores below the Basic category. |

| Approaching Advanced A |

29.1 97% |

Components are a mostly even split between Basic and Advanced/Proficient categories. No scores below the Basic category. |

| Basic Plus A |

28.2 94% |

Most components fall in the Basic category with some also falling in the Advanced/Proficient category. No more than 1 component falls in the Developing category. No scores are in the Emergent or Incomplete categories. |

| Basic A |

27.6 92% |

Most components fall in the Basic category with some falling in the Developing category. No scores are in the Emergent or Incomplete categories. |

| Approaching Basic B+ |

26.7 89% |

Components are fairly equally split between the Basic category and the Developing category. No more than 1 score is in the Emergent or Incomplete categories. |

| High Developing B |

25.5 85% |

Components mostly fall in the Developing category with some falling in the Basic category and no more than 1 score in the Emergent or Incomplete categories. |

| Low Developing B- |

24.6 82% |

Components mostly fall in the Developing category with some also falling in the Emergent category and no more than 1 score in the Incomplete category. |

| High Emergent C+ |

23.4 78% |

Components are split between the Emergent and Developing categories with no more than 1 score in the Incomplete category. |

| Emergent C |

22.5 75% |

Components mostly fall in the Emergent category with 2 or more scores in the Incomplete category. |

| Unsatisfactory Below C |

19.5 or less 65% or less |

Components mostly fall in the Emergent category with more than 2 scores in the Incomplete category. If your score falls in this category, the professor will request a meeting and will likely ask you to resubmit this assignment. |

| *please note: the descriptions for each grading category are not rigid. The instructor will use experience and expertise to evaluate your final grading category and earned points for this assignment. | ||

We implemented this early grading system for a few semesters. In this system, rubrics aligned to our course objectives, but this alignment was not explicitly stated on the rubrics. We felt that this approach for assessment was not moving students toward greater ownership of their grades or understanding the relationship between course objectives and rubric components because ultimately, all assignments were still graded with points, and those points were converted into a percentage at the end of the semester. We were getting closer, but more needed to be done to improve students’ metacognitive reflection of their own learning. We searched for a way to bring more meaning to grading and to keep students focusing on their learning rather than their grades. To accomplish this, we decided we needed to fully embrace SBG and remove the use of points altogether. In this paper, we describe six steps we used to transition our special education math methods course from a traditional to a no-points, standards-based grading system. We outline the badging system we used and the subsequent impact it had on our instruction and student learning.

Making the Transition to No-Points SBG with Badging

As we reflected on our course, we wanted to engage students in the process of deep learning, strong metacognition, and reflection. Acknowledging that our students live in a digital age where graphics and gamification are commonplace, we implemented badging because of the aesthetic value of badges in our current culture. Badging is relatively new to the field of education and is primarily used as a way to motivate and share accomplishments related to skill or merit (Ostashewski & Reid, 2014). From conversations with our students, we learned that they struggled to take ownership of their learning. Students noted that they passively accepted the learning that occurred in the course and were missing that deeper level of understanding they desired. While they could find or identify the course objectives in the syllabus, when asked, they could not reflect on them or explain how they related to the learning in the course. It seemed that students were consistently asking about their grades and their metacognition for their own learning was weak to nonexistent. In order to revamp our course, we implemented six steps: (a) familiarize and redefine course outcomes, (b) evaluate and align assignments and activities, (c) create rubrics, (d) establish a recording system for badges, (e) initiate the communication cycle, and (f) define final course grades.

Familiarize and Redefine Course Outcomes

To begin, we started looking through the standards outlined by the department for the course and clustered them into common themes. Identifying what we wanted students to learn and not how they would earn grades was an important first step in transitioning to SBG (Brookhart, 2011). After we simplified the list of standards into themes, we rewrote them into the course outcomes (see Figure 2). It is important to note the learning outcomes were not written so specifically to describe exactly how they would be measured. The outcomes, instead, needed to be flexible enough to evaluate them in multiple ways across all of our assignments. Next, we took these course outcomes and identified the main words that described them. Narrowing down the outcomes to a single word or phrase encapsulated what we wanted the ultimate outcome to include for the semester. For example, our course had many standards related to instructional approaches for learners with disabilities including the use of explicit instruction, providing appropriate feedback, utilizing visual representations, and collaborating with other professionals. Rather than listing out all individual standards or practices, we simplified these as one construct: pedagogy. These constructs became our badges that were easily identifiable for students. The following badges emerged as items we found important for our students to leave our class understanding: disability, mindset, diverse needs, pedagogy, math content knowledge, technology, and reflection.

Student Learning Outcomes:

By the end of the semester, you will complete a range of assignments that align with the following outcome areas:

- DISABILITY: understand and describe ways disabilities can impact math achievement

- MINDSET: utilize asset-based thinking and develop/maintain a growth mindset toward mathematics and teaching students with disabilities

- PEDAGOGY: plan, describe, and evaluate elements of explicit instruction and PBL in written lesson plans and lesson observations

- MATH KNOWLEDGE & PRACTICES: plan and practice evidence-based math strategies and appropriate mathematical representations to support declarative, procedural, conceptual, and problem-solving domains of knowledge

- DIVERSE NEEDS: develop differentiated lesson plans and instructional materials based on math standards, IEP goals, formative assessment of student strengths and needs, and research-based guidelines

- TECHNOLOGY: integrate appropriate assistive and instructional technology (both high- and low-tech) to support diverse learning needs within UDL and TPACK frameworks

- REFLECTION: self-reflect on the planning and execution of evidence-based math instruction

Evaluating and Aligning Assignments and Activities

Once we had a solid understanding of what we wanted to students to learn, it was time to evaluate our existing activities and assignments from prior semesters to see how they fit into our new framework. This gave us a chance to examine the course outcomes through the lens of what we wanted our students to achieve as a result of their learning in our course rather than what specific assignments we wanted them to complete. In our evaluation, we found most of our major assignments aligned well with our new outcomes, but some of the components on the rubrics did not match up with one of the outcomes. Using our old rubrics, we went through the language in the rubric component descriptions and matched them with our badge constructs. If there were components we were assessing that were not part of the course outcomes, we removed them. Then we looked to see which badge areas were missing from the existing assignments and assessments and brainstormed how to evaluate each course outcome across all assignments. By doing this, we ensured that all assignments aligned to all course outcomes and allowed us to meet our standards. Some outcomes were assessed more heavily on some assignments than others, but each outcome area (i.e., badge) was assessed on every major summative assignment.

A similar process was used to evaluate the alignment of some of the course activities each week. Over many semesters, a collection of in-class activities became routine to include, but we needed to make sure our time was well spent. Through our evaluation, we ended up removing several in-class activities and adding some new activities that better aligned with our outcomes. These activities were different than the major assignments in that they were used for formative, rather than summative, assessment of student learning. Though these activities were not graded, we believe they were important learning opportunities. We wanted students to see the value of the activities and how they aligned with their learning of the course outcomes, so we built in multiple opportunities for students to reflect on the activities’ alignment with the outcomes and conduct a self-evaluation on their learning toward those outcomes.

Creating the Rubrics

Once the activities and assignments were aligned with course outcomes, we created rubrics to specify observable criteria for mastery of each outcome on the assignments. We used the same holistic standards-based indicator levels for every assignment (see Figure 3 for an example rubric).

Student Learning Outcomes:

| Incomplete (I) | Developing (D) | Meeting (M) | Exceeding (E) |

|---|---|---|---|

| May be missing or has misunderstood the criteria for this section. | Has not yet met all of the described criteria. May have errors/misconceptions or may require more detail to demonstrate sufficient understanding. | Demonstrates a sufficient understanding of the described components for this section. All required components are explicitly present. Applies knowledge gained from the course, instructor feedback, and course materials. | Demonstrates an advanced understanding of the components for this section. Goes above and beyond minimum requirements and draws from knowledge and skills beyond what was covered in this course. |

Self Rating Directions: Use the rubric to self-evaluate your Vosaic lesson reflection by writing the letter that corresponds with your rating in the appropriate column. Provide a rationale as needed – NOTE: you must provide a rationale if you rate a component at the Exceeding level.

| Criteria sorted by outcome areas | Your Rating | Instructor Rating | Qualitative Rationale and/or Instructor Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Area 1: DISABILITY | |||

| Individual Differences – Within one or more timeline rows (may be in the “other” row), reflects on how disabilities or individual strengths/needs impacted student learning during the lesson | |||

| Outcome Area 2: MINDSET | |||

| Language – all annotations utilize person-first, asset-based, and/or growth-mindset language | |||

| Outcome Area 3: PEDAGOGY | |||

| Evidence-Based Practices – accurately identifies and thoughtfully reflects on the quality of execution of at least 3 different evidence-based practices that are appropriate for scaffolded PBL | |||

| Co-Teaching, Grouping Strategies, and Differentiation – Thoughtfully and accurately reflects on the co-teaching model, grouping strategies, and differentiation strategies selected and how well they helped enhance (or diminish) the lesson and meet the needs of the students. Offers specific suggestions on how to improve this in future lessons. | |||

| Monitoring Understanding & Facilitating Discourse – Thoughtfully reflects on how well they monitored and facilitated student understanding including their use of probing questions to guide their inquiry. Additionally evaluates and reflects on the levels of discourse as well as any missed opportunities for discourse. Offers specific suggestions for improving this in future lessons. | |||

| Outcome Area 4: MATH KNOWLEDGE & PRACTICES | |||

| Math Content Knowledge – Thoughtfully reflects on their own demonstration of content knowledge including mathematical accuracy, use of academic language, clarity of explanations, noticing of student errors and misconceptions, and ability to answer student questions | |||

| Outcome Area 5: DIVERSE NEEDS | |||

| Assessment – Showcases moments of student understanding and confusion with a reflection of their instructional practices that may have led to that. Discusses assessment of students at the class and individual levels. | |||

| Outcome Area 6: TECHNOLOGY | |||

| Instructional Materials – Within one or more timeline rows (may be in the “other” row), reflects on the quality, appropriateness, and facilitation of the technology/instructional materials | |||

| Outcome Area 7: REFLECTION | |||

| Overall Reflection – Tagged/annotated moments accurately represent what is happening in the video. Ample moments tagged for each prompt that represent a range of strengths and areas for improvement. | |||

| APA References – Connects reflection to both major course resources. Evidence-based practices are correctly cited in-text. | |||

The rubrics were created so that student self-assessment was paramount to the process in addition to instructor evaluation and feedback. Each section of the rubric was assessed by the student and the professor as incomplete, developing, meeting, or exceeding; however, the rubric did not provide criteria for each indicator level. Alternatively, only the requirements for meeting were provided. The students were prompted to reflect on what meeting the badge meant and decide if they accomplished that. If they did not meet the criteria, but made some progress toward it, then they were rated at the developing level. If they did not address the criteria listed, they were rated at the incomplete level. In order to earn an exceeding level, students needed to show deeper understanding for the badge area and include a rationale for how they exceeded the described criteria. For example, in a lesson plan, students are required to make three accommodations for learners to earn meeting on the rubric. In order to achieve exceeding status, students could include five, well-developed accommodations, a student-specific modification within this area, or connect to content in other courses. In order to earn an “A” in the course, in addition to meeting the course outcomes by earning badges, a student needed to earn at least 12 exceeding stars throughout the semester to show self-directed learning.

As noticeable on the example rubric, some learning outcomes had multiple criteria required to earn the badge. Generally, in order to earn an outcome badge for an assignment, a student had to earn at least meeting on all criteria aligned to that outcome. If a student did not earn a badge for an outcome area the first time, they had the opportunity to revise within a given timeframe utilizing instructor feedback (see explanation of “tokens” later in this article). Most students took advantage of this second opportunity to demonstrate their understanding of the outcomes to the instructor.

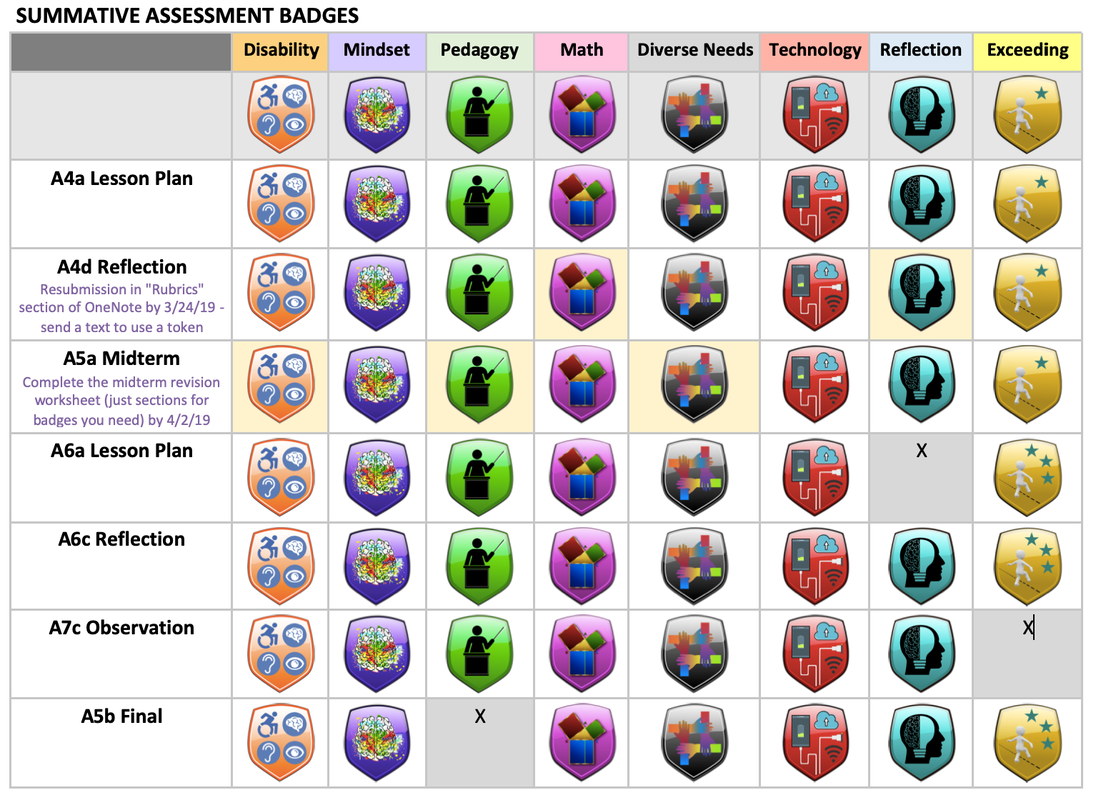

Establish a Recording System

This new format for grading required us to find an innovative way for sharing the badges with students because most Learning Management Systems (LMS) are not equipped for non-traditional grading methods. At our institution, faculty and students are provided access to Microsoft Office 365, so we decided to use OneNoteÒ Class Notebook for badge tracking. We decided that this would be a safe and secure way for sharing progress with students as opposed to online badge-tracking applications that would not adhere to student privacy guidelines set by the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). In OneNoteÒ, we were able to create Badge Tracker pages for each individual student (see Figure 4). On these pages, the badges were listed across the top of the column and all summative assignments were listed down the left side. Students could see which badges they had earned by assignment. If a student did not attain a badge with their first submission, that particular cell in the Badge Tracker was highlighted in order to see which areas needed improvement. After the established period of time for revision, the student either earned the badge with their revision or an “X” was placed in that cell, symbolizing that the badge was no longer available. Students could not see the Badge Tracker of other students in the class nor could they edit the page. On the Badge Tracker, students also had access to a key explaining the conversion of badges to course grades (see Figure 5).

Initiate the Communication Cycle

In addition to providing a FERPA-compliant method of tracking badges, OneNote® also allowed for two-way, ongoing communication between students and the instructor throughout the semester. The communication cycle was initiated when the students completed their rubric self-assessing themselves on each badge area and provided a rationale. The next step in the communication cycle was when the professor provided feedback on OneNote® using the rubric. Students had several options for continuing in the communication cycle after feedback was received. They could accept the feedback as written and complete no revisions, or they could submit a “token” to revise their work. Students started the semester with five “tokens” that could be used as second chances in a variety of ways. We encouraged students to save these tokens for assignment revisions allowing them additional opportunities to learn from feedback and demonstrate their learning. Other options for these tokens was to request a short extension on an assignment due date (arranged ahead of time), to make up a missed completion-based assignment (e.g., watching a flipped video), or to allow for an additional excused absence beyond the two allowed without grade penalty. We noticed our strongest students tended to save tokens for revisions, which we consider to be continuing the feedback communication cycle. Within this format, students do not receive an isolated grade and then move on. Rather, they come back to their learning throughout the semester in order to revise or reflect on their progress with the course outcomes.

Defining Final Course Grades

The final step in implementing no-points, standards-based grading with badging involved defining final course grades. Though we would be more satisfied with a system that does not use letter grades, we know this is not a reality at the moment. We considered different options for assigning a grade at the end of the semester that would reflect student learning while also crediting their efforts toward learning throughout the semester. The summative assignments were simple to include in a final course grade. Knowing that students had the opportunity to demonstrate their learning of an outcome on every summative assignment, we decided that to earn an “A,” students could miss no more than four badges overall with no more than one missing badge on any assignment or outcome area. Trickier to consider in a final grade were formative assessments like technology-based quizzes, journal entries, reflections on course activities, worksheets to practice specific math strategies, and embedded responses on flipped video content. We wanted students to see the value in working hard and reflecting on these activities as well, so those activities were sorted into different areas and used as “completion badges” that were also considered in their final course grade. Included within the completion badges was a “logistics” badge that could only be earned if a student followed directions on assignments and submitted all assignment on time. In Figure 5, we show our final grading scale that includes summative badges, completion badges, and exceeding stars (earned for rubric components on which students exceeded the given criteria). While this grade conversion is not perfect (we are still reflecting/revising in the current semester), we believe the final course grades earned truly reflect student learning. Additionally, by embedding regular opportunities for reflection on learning through journaling, surveying, class discussion, self-rating, and assignment revisions, we believe our students are beginning to shift their thinking to learning over grades.

| Grade Earned | Criteria |

|---|---|

| A |

|

| B |

|

| C |

|

| D |

|

| F |

|

Discussion

We found badging to have several benefits to our instruction and student outcomes as noted by student performance, debriefs with our classes, and anonymous course feedback. The first benefit we identified was student understanding of what they were learning in the course. We found they were able to have conversations about and reflect on learning of the course outcomes (i.e., badges) informally and formally with their professor and peers as Boesdorfer, Baldwin, and Lieberum (2018) described. For example, on both the midterm and final reflections, all students were able to describe course activities related to each outcome area and reflect on their own learning and areas for improvement in each area. Class discussions were enhanced though common language as students understood the overarching goals of the course.

An additional benefit we found from this process was the uniformity achieved across course sections. Carifio and Carey (2009) noted one benefit of standards-based grading the creation of a coherent and uniform approach to grading. With well-defined course outcomes, we were able to share and communicate more effectively with all course instructors which led to consistency in student learning regardless of the section in which a student was enrolled. As different teachers were assigned to the course, the vision for the course was consistent throughout all sections.

After working with badging for an entire academic year, we have found ways to allow for individual nuances in delivery while adhering to the system as a whole. We are all using the same badges (i.e., outcomes) for the course, but plan to allow for professors’ discretion on the layout of the Badge Tracker and conversion to a final course grade moving forward. With our increased familiarity of the badging system, we can reflect and make more expeditious decisions. For example, one recent iteration of badges has adjusted the number of badges associated with each assignment to serve as a form of assignment weighting. Though weighting may seem counter-intuitive to standards-based grading efforts, we know some assignments require more work and more opportunities to demonstrate learning in each outcome area than others. We look forward to analyzing data collected each semester to better understand how these revisions to our grading system may influence student perceptions of learning and assessment.

As a new semester is upon us and we have reflected on the successes and challenges of using standards-based grading with a badging system, we feel confident going forward and introducing this to a new set of students. We also feel comfortable allowing our evaluation methods to evolve. We hope the six steps we have introduced here will help you reflect on your assessment philosophy and guide you on your own transformative journey.

References

Adams, J. B. (2005). What makes the grade? Faculty and student perceptions. Teaching of Psychology, 32(1), 21–24. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top3201_5

Boesdorfer, S. B., Baldwin, E., & Lieberum, K. A. (2018). Emphasizing learning: Using standards-based grading in a large nonmajors’ general chemistry survey course. Journal of Chemical Education, 95(8), 1291–1300. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00251

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Starting the conversation about grading. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 10–14.

Carifio, J., & Carey, T. (2009). A critical examination of current minimum grading policy recommendations. The High School Journal, 93(1), 23–37. doi: 10.1353/hsj.0.0039

Guskey, T. R. (2001). Helping standards make the grade. Educational Leadership, 59(1), 20–27.

Marzano, R. J. (2000). Transforming classroom grading. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Muñoz, M. A., & Guskey, T. R. (2015). Standards-based grading and reporting will improve education. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(7), 64–68. doi: 10.1177/0031721715579043

O’Connor, K., & Wormelli, R. (2011). Reporting student learning. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 40–44.

Ostashewski, N., & Reid, D. (2015). A History and Frameworks of Digital Badges in Education. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (Eds.), Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 187–200). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_10

Tippin, G. K., Lafreniere, K. D., & Page, S. (2012). Student perception of academic grading: Personality, academic orientation, and effort. Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(1), 51–61. doi: 10.1177/1469787411429187

Boesdorfer, S. B., Baldwin, E., & Lieberum, K. A. (2018). Emphasizing learning: Using standards-based grading in a large nonmajors’ general chemistry survey course. Journal of Chemical Education, 95(8), 1291–1300. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00251

Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Starting the conversation about grading. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 10–14.

Carifio, J., & Carey, T. (2009). A critical examination of current minimum grading policy recommendations. The High School Journal, 93(1), 23–37. doi: 10.1353/hsj.0.0039

Guskey, T. R. (2001). Helping standards make the grade. Educational Leadership, 59(1), 20–27.

Marzano, R. J. (2000). Transforming classroom grading. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Muñoz, M. A., & Guskey, T. R. (2015). Standards-based grading and reporting will improve education. Phi Delta Kappan, 96(7), 64–68. doi: 10.1177/0031721715579043

O’Connor, K., & Wormelli, R. (2011). Reporting student learning. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 40–44.

Ostashewski, N., & Reid, D. (2015). A History and Frameworks of Digital Badges in Education. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (Eds.), Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 187–200). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_10

Tippin, G. K., Lafreniere, K. D., & Page, S. (2012). Student perception of academic grading: Personality, academic orientation, and effort. Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(1), 51–61. doi: 10.1177/1469787411429187

© 2019 Illinois State University